Social engineering secrets that everyone needs to know (part 1)

Understanding and Overcoming Social Engineering Tactics

Social engineering represents a sophisticated manipulation technique that coerces individuals into performing actions or divulging confidential information against their interests. It exploits human vulnerabilities rather than technological flaws, as dramatically illustrated by the Rotherham case from 1997 to 2013, where predators exploited over 1,400 children using simple lures like ice cream, car rides, alcohol, and marijuana. These simple tricks underscore the technique's potency in manipulating human behaviour for appalling ends. Social engineering can also be used to gain illicitly sensitive and critical information like personal identifiers, such as passwords and social security numbers, to corporate secrets and state-level intelligence.

How Social Engineering Works?

The short answer is simply that our brain likes to simplify a large, complex amount of information. Just like your brain is now trying to scroll to the end of the article while only reading the subtitles in order to simplify complex information and come to its own conclusion. Afterwards, the brain releases dopamine as a pat on the back for the hard work you have done, falsely claiming that you now understand social engineering and you are an expert in the field. Joke aside, these cognitive biases are a normal part of human thinking and are exploited by those seeking to manipulate through social engineering. These individuals know a great deal about human behaviour and manipulate by exploiting emotions like greed, generosity, fear, and curiosity.

The Heuristic Effect

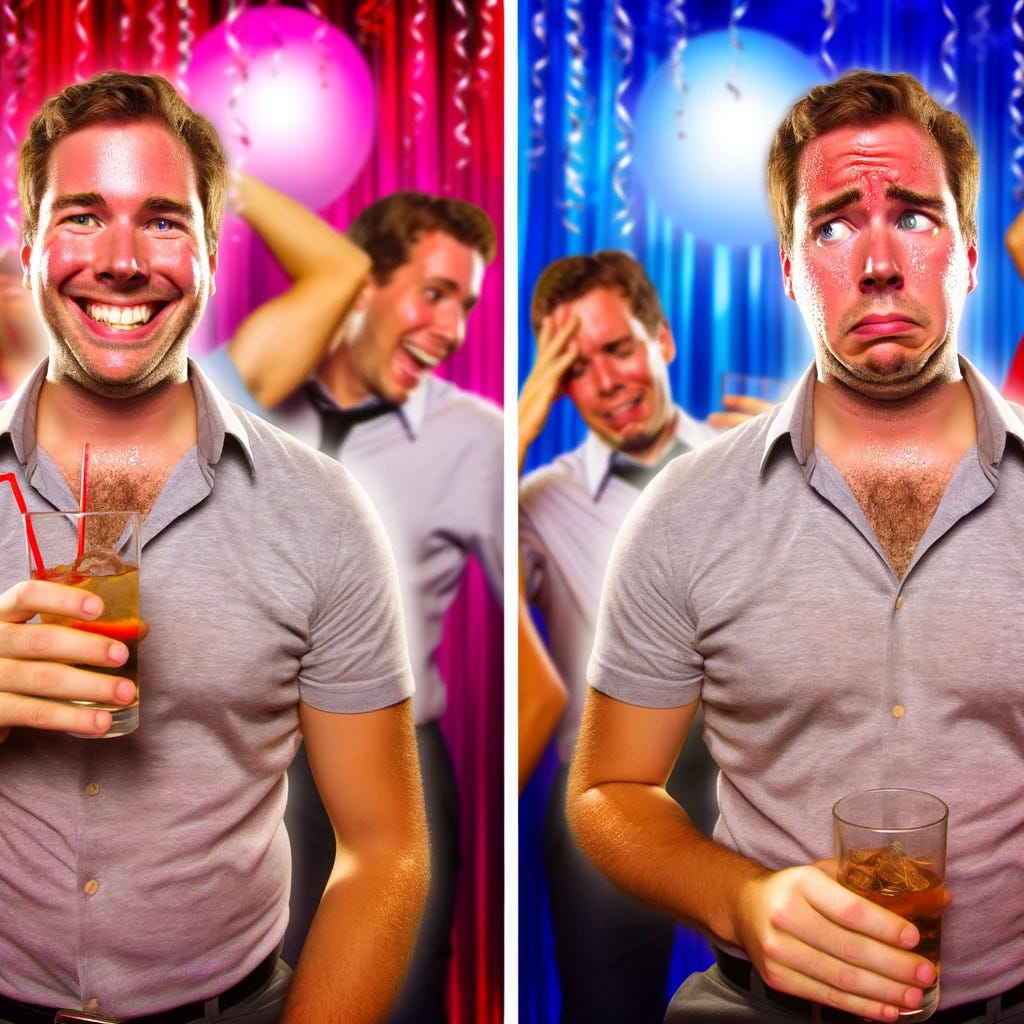

The heuristic effect is what most people call a gut reaction. It is that fast, often instantaneous, reaction to something that helps you make a decision based on intuitive feelings rather than analytical reasoning. If you feel good about something, you assume that something is good, and vice versa. This instinctual process is deeply rooted in our evolutionary history, where quick decision-making could mean the difference between survival and peril. It is a mechanism that allows us to navigate a complex world with efficiency, relying on immediate emotional responses to guide our actions. When we encounter a situation, our brain rapidly assesses past experiences, emotions, and perceptions to produce a gut feeling. This feeling then influences our decision, leading us to embrace or avoid similar situations in the future without the need for deliberate analysis.

For example, if you have consistently enjoyed social gatherings, finding them to be sources of joy and connection, you are likely to have a positive gut reaction to invitations, associating them with good experiences. Your brain simplifies the decision-making process by recalling the positive emotions associated with past events, prompting you to expect similar outcomes in the future. Conversely, if you have experienced social anxiety or discomfort at such events, your gut reaction might be one of apprehension or avoidance, as your brain quickly concludes that the negative feelings might recur. This heuristic approach, while efficient, can sometimes lead us astray, particularly when our past experiences are not accurate predictors of future outcomes, underscoring the complex interplay between intuition and rationality in human decision-making.

As a second example imagine you have always found mathematics challenging and struggled with it during your school years, leading to feelings of frustration and inadequacy. Now, as an adult, when presented with the opportunity to learn a new skill that involves mathematical reasoning, such as coding, your initial gut reaction might be apprehension or outright avoidance. This instinctual response, rooted in your past experiences with mathematics, might lead you to assume that coding will be just as challenging and unpleasant, even though it is a different discipline and you might have the capacity to excel in it with the right approach and mindset. Conversely, if you had excelled in mathematics and enjoyed solving complex problems, you might view the prospect of learning coding as an exciting and rewarding challenge, eagerly anticipating the opportunity to expand your skills.

Decoy Effect

The Decoy Effect is a fascinating principle from behavioural economics that demonstrates how the presence of a third option (option C, the decoy) can influence our decision-making process when we are initially presented with two choices, option A and option B. This effect capitalises on our comparative judgement system, making one of the original options more attractive by introducing a third option that is specifically designed to be inferior in some key aspects but closely related to one of the original choices.

When faced with just two options, our decision can often feel challenging because each option will have its strengths and weaknesses, making it hard to decide which is more valuable or suited to our needs. However, the introduction of a third option, the decoy, is strategically priced or featured to make one of the initial choices appear more appealing by comparison. The decoy is not necessarily meant to be chosen but rather to skew the perception of the other options, altering our decision-making process.

This effect plays on the human tendency to compare options relative to one another. When option C is introduced, it is usually similar but slightly inferior to one of the options (often option B), making option B look better in direct comparison than it did when compared only with option A. As a result, people are more likely to choose option B over option A, a choice they might not have made without the presence of the decoy. This clever manipulation of choices can significantly influence consumer behaviour, guiding people towards a decision that they believe is the best value, based on the comparative advantage highlighted by the decoy effect.

Imagine you are booking a flight and are presented with two seating options: a standard economy seat priced at £150 and an economy plus seat with extra legroom priced at £200. Initially, you lean towards the standard economy for its affordability. However, the airline introduces a third option: a premium economy seat that not only offers extra legroom but also includes priority boarding and complimentary drinks, priced at £250.

This new option C (the decoy), the premium economy seat, serves as the decoy. While it is more expensive and perhaps more luxurious than what you initially considered, it makes the economy plus seat (option B) appear more attractive in comparison to the standard economy seat (option A). The economy plus seat now seems like a judicious middle ground, providing additional comfort for a modest price increase, making it appear as a better value compared to before the introduction of the premium economy option. Consequently, you might find yourself more inclined to choose the economy plus seat, perceiving it as the optimal balance of cost and comfort, thanks to the altered value perception introduced by the decoy of the premium economy seat. This example illustrates the Decoy Effect, where the introduction of a third option can significantly influence your preference between the two original choices by shifting your perception of their relative value.

Another example of the Decoy Effect involves movie streaming service subscriptions. Consider you are evaluating two subscription plans: a Basic plan priced at £7.99 per month, which allows streaming on one device at a time in standard definition, and a Standard plan priced at £9.99 per month, offering streaming on two devices simultaneously in high definition.

The streaming service then introduces a third option: a Premium plan for £11.99 per month, which allows streaming on four devices simultaneously in ultra-high definition. This new option (C), the Premium plan, acts as the decoy. While it is the most expensive and offers more than what you initially might need, it enhances the attractiveness of the Standard plan (option B) in comparison to the Basic plan (option A). The Standard plan now appears to be the "sweet spot," offering a significant upgrade in quality and flexibility for a relatively small increase in price, especially when considered against the higher-priced Premium option.

Thus, you might be more inclined to choose the Standard plan, seeing it as the best compromise between functionality and cost, influenced by the altered value perception that the Premium plan introduces.

The Ostrich Effect

People will pick and choose what information they want: If it is positive, they can never get enough, but they will avoid even helpful information if it happens to be negative. It is a bit like saying that if you cannot see something, it is not there. This behaviour, where individuals selectively engage with information based on its emotional valence, underscores a fundamental aspect of human psychology: the tendency to favour comfort and positivity over discomfort and negativity, even when the latter might be beneficial in the long term. This selective attention to information serves as a coping mechanism, allowing individuals to maintain a sense of optimism or avoid immediate distress. However, this avoidance can have detrimental effects, as it often delays necessary actions or adjustments that could mitigate or resolve underlying issues.

The metaphor of burying one's head in the sand, akin to an ostrich — which is actually a myth about the bird's behaviour — vividly illustrates this avoidance strategy. It conveys how people, confronted with potentially distressing or unfavourable information, choose to ignore it, pretending it does not exist. This approach is a psychological defence mechanism aimed at preserving one's current state of mind or avoiding the anxiety associated with confronting difficult truths.

A good example of the Ostrich Effect is the avoidance of medical check-ups. Imagine a person who suspects they might have a health issue, perhaps because of persistent symptoms, but chooses not to visit a doctor for a diagnosis. Despite knowing that early detection and treatment could lead to a better outcome, the fear of receiving bad news leads them to avoid making an appointment. This avoidance is a classic case of the Ostrich Effect: by not seeking medical advice, the individual behaves as though the potential health issue might not exist, hoping to avoid the anxiety or unpleasantness associated with a possible negative diagnosis. This deliberate ignorance can delay necessary treatment, demonstrating how the Ostrich Effect can have serious implications beyond financial or minor personal matters.

Another very common example of the Ostrich Effect is seen in individuals avoiding checking their bank accounts or financial statements after a period of heavy spending, such as during the holidays or after a vacation. Despite knowing that overspending may have led to a depleted savings account or increased credit card debt, they choose not to look at their financial statements. This avoidance stems from a fear of confronting the reality of their financial situation, hoping that if they do not see the numbers, they can delay dealing with the stress and anxiety associated with financial strain. By ignoring their financial status, they engage in a form of wishful thinking, as if the act of not observing the problem could somehow make it less real or severe. This behaviour exemplifies the Ostrich Effect, where the discomfort of potentially negative information leads to a deliberate avoidance of facing facts, even though early acknowledgment could prompt necessary budget adjustments or financial planning to mitigate the issue.

The Optimism Bias

Optimism is a wonderful thing; it helps us move forward in our lives. However, it is not good to let optimism stop us from being realistic. We tend to expect things to turn out really well, in fact, a lot better than they often do in reality. This is because our pre-programmed tendency is to look at the future optimistically. However, it can mean we fail to prepare for the negative, leaving us potentially vulnerable and exposed to potential danger.

An example of optimism bias can be observed in the context of starting a new business. Many entrepreneurs enter the market with high hopes and expectations for their business venture's success. Fuelled by stories of startups that quickly turned into multi-million-pound enterprises, they might overlook the statistical reality that a significant percentage of new businesses fail within the first few years. This optimism bias leads them to underestimate the challenges and potential obstacles, such as market competition, customer acquisition costs, or operational issues. They might neglect to create a comprehensive business plan, fail to secure adequate funding for long-term sustainability, or not have a contingency plan in place for potential setbacks. While optimism is crucial for driving innovation and taking the leap into entrepreneurship, an unchecked optimism bias can result in inadequate preparation and risk management, leaving the entrepreneur vulnerable to the harsh realities of the business world.

Another example of optimism bias is evident in personal savings and retirement planning. Many individuals assume they will have plenty of time to save for retirement or believe that they will need less money in their retirement years than is realistically required. This optimism leads them to postpone saving or to save less than is advisable, under the assumption that future circumstances will somehow align to make up for the shortfall. They might also overestimate their ability to continue working or to generate income well into what traditionally would be considered retirement age, neglecting the potential for unforeseen health issues, job market changes, or economic downturns that could affect their ability to earn. This bias towards an overly positive outlook can result in insufficient funds for a comfortable retirement, forcing individuals to adjust their lifestyle significantly or rely on external support in later years. Recognising and addressing optimism bias in financial planning is crucial for securing financial stability and independence in retirement.

The Recency Bias

This phenomenon, where recent events and trends disproportionately influence our perceptions and decisions, is known as recency bias. It is a cognitive bias that affects how we process information, remember experiences, and make predictions about the future. Recency bias leads us to give more weight to the latest information we receive, under the assumption that these recent events or trends provide the most accurate indication of what is to come. This can be particularly evident in how we react to news, financial markets, weather patterns, and even personal experiences.

For example, in the financial realm, investors might see a short-term rally in the stock market and conclude that the upward trend will continue, prompting them to make investment decisions based on this limited view. Similarly, after experiencing a particularly mild winter, people might downplay the likelihood of severe winter storms in the future, affecting their preparedness for such events.

Recency bias can lead to a lack of preparedness for sudden changes, as it discourages us from considering a broader range of data or historical patterns that might offer a more nuanced perspective. By focusing too narrowly on the most recent information, we may overlook important trends or warnings that are essential for making well-informed decisions. This bias toward the present and the immediate past can make it challenging to plan effectively for the future, especially in situations where conditions are dynamic and unpredictable. Recognising and mitigating recency bias involves actively seeking out and considering a wider array of information, including data from different time frames and sources, to foster a more balanced and comprehensive understanding of the situation at hand.

An example of recency bias can be observed in the cryptocurrency market, where the volatility and rapid price changes are even more pronounced than in traditional stock markets. For instance, if a particular cryptocurrency has seen a significant surge in value over recent weeks or months, investors, influenced by recency bias, might conclude that this upward trend will continue for the foreseeable future. Consequently, they may decide to invest a substantial portion of their portfolio into this cryptocurrency, often neglecting the inherently volatile nature of digital currencies and the historical cycles of booms and busts within this market.

This tendency to focus on recent performance can lead investors to overlook the need for diversification, placing a disproportionate amount of their investments in cryptocurrencies without adequately considering the risks. When the cryptocurrency market undergoes a correction or enters a bear phase, which it frequently does, these investors can face substantial losses. Their decision, driven by recency bias, to heavily invest based on short-term trends rather than a balanced assessment of long-term potentials and risks, leaves them particularly vulnerable to the market's rapid and unpredictable shifts.

Recency bias in cryptocurrency investing underscores the importance of a well-considered strategy that accounts for the market's historical volatility and the unpredictable nature of digital currencies, rather than relying solely on the latest trends.

Another example of recency bias, compounded by a lack of personal experience with a specific type of disaster, can be seen in the context of the unprecedented freeze that struck Texas in February 2020. Prior to this event, many residents of Texas might not have considered the risk of severe winter weather seriously, given the state's typically mild winter climate. This lack of personal experience with such disasters could lead to underestimating the likelihood of their occurrence and, consequently, a lack of preparation for winter emergencies.

When the "Big Freeze" hit, the infrastructure was unprepared for the extreme cold, leading to widespread power outages, water supply problems, and significant discomfort and danger for residents. This event starkly illustrates how recency bias, coupled with a lack of direct experience with certain types of natural disasters, can result in inadequate preparedness. People may ignore the risks of disasters they have not personally encountered before, assuming that if it has not happened recently, or ever in their lifetime, it is unlikely to happen at all.

Following the disaster, there might have been a surge in interest and investment in winter preparedness measures, such as insulating homes and securing backup power sources. However, as time passes without another similar event, recency bias may lead individuals to once again become complacent, potentially neglecting these preparedness measures under the assumption that another freeze of such severity is unlikely to recur. This cycle of reaction and complacency underscores the challenge of maintaining a consistent level of preparedness for rare but impactful events.

Strategies for Overcoming Social Engineering Biases

In light of the vulnerabilities exposed by social engineering tactics and our inherent cognitive biases, it is crucial to develop strategies that empower us to safeguard our decision-making processes. By understanding how these biases influence our behaviour, we can implement measures to mitigate their effects. Below, we outline step-by-step advice tailored to counteract each bias discussed in this article:

The Heuristic Effect

Pause and Reflect: Before reacting instinctively, take a moment to consider the rationale behind your inclination. Is it based on solid reasoning, or merely an emotional impulse?

Seek Objective Input: Discuss your situation with a trusted third party. An outside perspective can dilute the bias of immediate intuition, guiding towards more analytical decision-making.

Educate Yourself: Learn about common social engineering scenarios. Recognising these can trigger a mental alert when you encounter something similar, prompting a more cautious response.

Decoy Effect

Clarify Needs and Preferences: Before evaluating your options, outline what you genuinely need or prefer in the given context, which helps in seeing past the superficial allure of a decoy.

Evaluate Independently: Assess each option on its own merits rather than in comparison to others, especially when a third choice seems to skew the balance.

Delay Decision: If possible, give yourself time before making a decision. Distance can diminish the immediate impact of the decoy, allowing for a clearer comparison.

Ostrich Effect

Implement Scheduled Reviews: Establish regular intervals for checking on aspects of life you might typically avoid, such as financial health or medical check-ups.

Leverage Automation: Use tools that automate essential but often avoided tasks, ensuring they are completed without your direct intervention.

Face Fears Gradually: Approach daunting tasks in small, manageable steps to reduce the psychological barrier they may present.

Optimism Bias

Create Contingency Plans: Always have a plan B. Optimism is a driving force, but realism ensures preparedness for potential setbacks.

Reality-Check Your Assumptions: Regularly compare your expectations against statistical realities and historical data to ground your optimism in realism.

Seek Diverse Perspectives: Expose yourself to viewpoints that differ from your own, especially more conservative or realistic ones, to balance your optimism.

Recency Bias

Broaden Information Sources: Actively seek information from a wide range of dates and contexts, not just the most recent or vivid examples.

Embrace Long-Term Planning: Engage in activities that require long-term planning and consideration, which naturally counters the short-sightedness of recency bias.

Reflect on Past Decisions: Regularly review decisions made in the past and their outcomes, focusing on the information that influenced those decisions. This reflection can reveal tendencies towards recency bias and help adjust future decision-making processes.

By integrating these strategies into our daily lives, we can enhance our resilience against social engineering attacks and make more informed, objective decisions. Recognising and addressing these biases not only protects us from manipulation but also enriches our personal and professional development.